N9149A wrote:... Pehaps if George would get carb ice more than once he might feel more like I do. I also apply full carb heat before and maintain full carb heat during any decent regardless of the atmospheric conditions.

Perhaps you didn't mean to, but it's insulting to suggest that with 13,000 hours, over half of them in carbureted airplanes, I don't have sufficient "experience" to know how to identify and deal with carburetor ice. I believe that my techniques (which are the same ones taught at the majority of schools) are better suited to dealing with carb ice, and is proven by the reduced number of times I've been surprised by it. (Also I never said I'd had carb ice only "once". I've just not been surprised by it because I've always detected it before it became a problem. Welll.... I take that back.... there was that time when I was a student pilot that it scared the bejeezus out of me. And I've never forgotten to monitor RPM since.) I'm sure you didn't mean it the way I first interpreted it, however.

I believe the practice of flying extensively with carb heat applied is not just overly cautious, but may even be hazardous. Unless a carburetor air temperature gauge is available, operating with carb heat applied over long periods and low power settings is not only less efficient and contributes to increased engine wear... it also may actually contribute to carburetor icing under certain conditions. These comments apply especially to the Owner's Manual comments regarding partial-application. Here's why: Without knowing the actual air temp in the carburetor, a pilot who applies carb heat as a continuously-preventive measure may actually raise air temperatures to the point of allowing moisture-laden air to come to the freezing point. In such case, the already cold air would have been too cold for ice to form except for the fact it was artificially warmed by the carb heat. AVOID use of partial carburetor heat. Use either FULL heat or NO heat, unless you have a CAT gauge.

This is not to suggest that our airplanes should all be equipped with Carb Air Temp (CAT) gauges. I don't believe they are necessary at all in such simple installations. Any ice formed will give adequate warning by producing a reduction of RPM. The problem is usually that of pilots who do not note and monitor RPM settings. (Referring to single-engine, Fixed pitch props. Multi-engined, carbureted, variable-pitch props are more needful of such CAT instrumentation, in my opinion. The early Martin 202/404 and some Convair airliners had them, as examples.)

Manifold pressure gauges are also useful tools in warning of carb ice in that they will demonstrate a loss of MP commensureate with fixed-pitch RPM loss. They will warn of ice with either fixed pitch or variable pitch props if they are properly monitored. I would rather have a MP gauge than a CAT gauge because it will aid in other engine diagnostic functions which CAT gauges will not. A CAT gauge is way down my wish-list.

Application of carb heat enrichens the mixture considerably and, if such practice is what one follows, the engine should be leaned for that condition. Flying along with carb heat applied actually reduces available power because it increases the apparent density-altitude for the engine. The engine thinks it's operating in the desert at high altitude, which causes a loss of horsepower. I am loathe to accept that in my airplane. If I want to fly with reduced power I will accomplish that with the throttle not the carb heat.

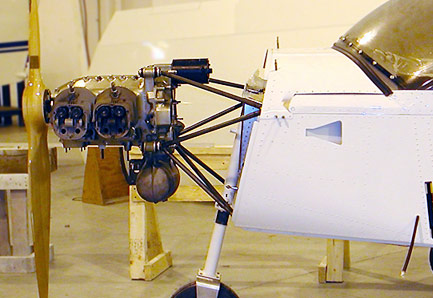

From a preventive-maintenance point of view, it's important to inspect the carb heat air passages regularly. The flexible hose (SCAT/SCEET) which introduces air to the heater muffs and to the carburetor air-box can be seen by insects/mud-daublers as wonderful habitat for building nests. Any subsequent application of carb heat can introduce those nests to the carburetor causing engine failure. This has happened in as little as two-days time from the last inspection. (Cessna 172 accident on takeoff from Brenham, two days after annual inspection which replaced the air-box.)

I've found air hoses which had the spiral wire rusted into loose pieces, ready to be consumed by the engine. (That's also why I only use double-walled, high-temp SCEET hose in my carb-heat circuit.) Those hoses are notorious for collecting water in the lower loops areas after airplane and engine washes. A big gulp of water in-flight can be a nerve-wracking experience, so check those hoses after washing down the engine and airplane. (Some folks recommend using an awl to pierce the hose at the lowest point to provide drain holes, but I don't go that far, I just inspect and loosen one end and lower it to drain it, using the opportunity to inspect the interior of the hoses for condition.)